Background

Solid organ transplantation is a life-saving procedure for individuals with end-stage organ disease. Outcomes among solid organ transplant recipients (SOTRs), while better than for those on the waiting list, have been affected by the lifelong need for immunosuppressive therapy to prevent organ rejection. In the United States, the number of transplants performed has risen over time from 15,000 in 1990 to 41,000 in 2021.

Cancer represents an important problem for SOTRs. Immune suppression plays an important role, since risk is quite high for two cancers clearly linked to immunosuppression, namely, non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) and Kaposi sarcoma. NHL is at the most advanced end of a spectrum of post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disorder driven by chronic Epstein-Barr virus infection. Cancer risk is also elevated for additional cancers caused by viruses (e.g., anogenital cancers caused by human papillomavirus) and for some infection-unrelated cancers, e.g., cancers of the lip, lung, thyroid, and kidney, as well as melanoma. Some of these increases may reflect contributions of transplant-related comorbid medical conditions, carcinogenic effects of medications, or other factors. Risk is not elevated for breast or prostate cancer.

Importantly, earlier studies of cancer risk in SOTRs generally suffered from incomplete cancer ascertainment, lack of statistical power, and/or inadequate data on risk factors of interest. Most studies of SOTRs evaluated only a limited number of individuals (typically 2000-6000) and/or restricted investigation to kidney transplant recipients. The studies of SOTRs lacked data on important cancer risk factors such as viral infections and immunosuppressive regimens.

Since the first organ transplants in the 1960s, it has been recognized that cancer can be transmitted from donors to recipients, either from primary tumors in the transplanted organ or from sub-clinical implants of tumor cells. Transmission has been most clearly documented in case series in which tumors in donors and recipients share characteristic features, or through use of specific tumor markers (e.g., identification of Y chromosome in a female recipient’s tumor). In light of this risk, individuals with a known history of most cancers are precluded from organ donation.

Relatively little is known about outcomes following a cancer diagnosis among SOTRs. Recurrence of such cancers following transplantation is of concern for two reasons. First, if immunity contributes to control of cancer, then transplant-related immunosuppression may facilitate cancer recurrence and worsen survival. Second, donor organs are a scarce resource, so potential transplant candidates with a history need to be carefully assessed to ensure that the cancer is well-treated and they are in remission, in order to avoid futile transplants. Additional information on cancer outcomes among SOTRs can help inform clinical management and transplant program decisions regarding waitlisting and transplantation.

The Transplant Cancer Match (TCM) Study is a linkage of the U.S. national solid organ transplant registry (i.e., the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients [SRTR]) with multiple U.S. state and regional cancer registries, to identify cancers in transplant recipients, wait list candidates, and donors. The TCM Study has several major advantages over prior investigations of cancer in SOTRs. First, it is large, including a substantial proportion of the US transplant population. Second, the recipients include all organs, not just kidneys, so we can directly compare cancer risk across various groups. Third, the study obtains data from cancer registries, providing largely complete ascertainment and allowing classification of malignancies into histological subtypes. Fourth, the SRTR includes data on various potential cancer risk factors (e.g., viral infections in recipients and donors, immunosuppression regimens) which can be examined in relation to cancer risk.

Objectives of the TCM Study

- Describe cancer risk in SOTRs and identify risk factors, including health conditions and specific medications.

- Characterize risk for transmission of cancer from solid organ donors to recipients.

- Characterize accuracy and completeness of transplant registry reports of cancer in SOTRs.

- Assess cancer treatment and outcomes following a cancer diagnosis among transplant SOTRs.

- Measure the burden of cancer in the transplant population and its contribution to the total burden in the general population.

- Evaluate cancer risk in individuals on the wait list for an organ transplant and among organ donors.

- Evaluate mortality from cancer and other causes among recipients, candidates, and donors.

Registry Data Sources

The TCM Study is a linkage of the SRTR with multiple state and regional cancer registries.

a. SRTR

Under the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) Final Rule, the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) is delegated by the Secretary of Health and Human Services to oversee the U.S. transplant network. This responsibility includes collecting data for surveillance purposes to ensure the safety of the transplantation process. For this purpose, HRSA’s contractor maintains a database, the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR), which contains information on all U.S. transplant recipients, waitlist candidates, and living and deceased donors.

Transplant centers and organ procurement organizations provide the data collected into the SRTR. For waitlist candidates and transplant recipients, information is provided on demographic characteristics, underlying medical conditions, and (at the time of transplantation) characteristics of the transplanted organ and donor. Follow-up data on graft failure and death (including cause of death) are reported after transplantation at 6 months, 1 year, and yearly after that. Transplant centers also report on the occurrence of malignancies, including basal and squamous cell skin cancer. Find a list of SRTR variables on the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients website.

b. Cancer Registries

Cancer is a reportable condition in every U.S. state, and hospitals, pathology laboratories, and physicians are required to report cancer diagnoses to state registries. Some cancer registries cover other geographic regions (e.g., the Seattle/Puget Sound region of Washington, which is a SEER cancer registry; Washington, DC; Puerto Rico). Cancer registries capture all diagnoses of invasive cancer (except basal and squamous cell skin cancer), most in situ cancers, and certain benign tumors (i.e., brain tumors). Information includes demographic characteristics, tumor characteristics (site, histology, stage), initial treatment, and mortality (including cause of death, typically ascertained through linkage to state and national death files). Find a list of variables collected by cancer registries.

c. Linkage Methods

TCM investigators have performed computerized data linkages of the SRTR and cancer registries based on name, social security number, date of birth, and sex. During the course of the study, these linkages have utilized deterministic matching (i.e., multiple combinations of variables in a ranked list have been compared for exact matches) or probabilistic matching (i.e., combinations of variables have been scored on the likelihood of being a true match). Linkages have been conducted variously by the SRTR, by individual cancer registries, or through the North American Association of Cancer Registries’ Virtual Pooled Registry (VPR). The VPR is a program to enable investigators to conduct linkages with multiple cancer registries.

Initially, the TCM Study included 13 cancer registries that were large and/or part of NCI’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program.1 We gradually enlarged the study with additional cancer registry linkages and updated linkages with participating registries. In 2019, investigators applied to conduct cancer registry linkages through the VPR program. VPR approval allowed the study to be substantially expanded and updated, so that the study currently includes data from 34 cancer registries, with data from 2 registries through 2018-2019 (see Table 1).

| Cancer registry | Start year of cancer registry data | End year of cancer registry data |

|---|---|---|

| AK | 1996 | 2017 |

| AL | 1996 | 2016 |

| AR | 1996 | 2016 |

| CA | 1988 | 2017 |

| CO | 1979 | 2016 |

| CT | 1973 | 2017 |

| FL | 1981 | 2019 |

| GA | 1995 | 2017 |

| HI | 1995 | 2017 |

| IA | 1973 | 2017 |

| ID | 1975 | 2017 |

| IL | 1986 | 2018 |

| KY | 1995 | 2017 |

| LA | 1995 | 2017 |

| MI | 1985 | 2018 |

| MT | 1979 | 2017 |

| NC | 1995 | 2016 |

| ND | 1997 | 2016 |

| NE | 1987 | 2017 |

| NJ | 1979 | 2016 |

| NM | 1973 | 2016 |

| NV | 1995 | 2015 |

| NY | 1995 | 2017 |

| OH | 1996 | 2015 |

| OK | 1997 | 2017 |

| OR | 1996 | 2016 |

| PA | 1995 | 2017 |

| Puerto Rico | 1985 | 2016 |

| RI | 1995 | 2015 |

| SC | 1996 | 2016 |

| Seattle | 1974 | 2017 |

| TX | 1995 | 2016 |

| UT | 1973 | 2017 |

| VA | 1995 | 2016 |

Data Editing and Quality Checks

Following linkages of the SRTR with each cancer registry, we receive an updated version of the SRTR dataset, a cancer registry file, and a crosswalk file indicating which SRTR record matched with each cancer registry case. These files contain ID numbers, so that investigators can communicate with the registries regarding individual records, but no personal identifying information. For instance, names and social security numbers are not included, and dates in the cancer registry are rounded to month and year.

We have implemented routine procedures to clean up the files by deleting or editing problematic records or matches. For example, these steps include:

a. Deleting cancer registry records where the cancer diagnosis date is outside the years of complete cancer ascertainment;

b. Deleting records with missing sex or age;

c. Deleting cancer records where the sex is discrepant with respect to the cancer site (e.g., prostate cancer in a female);

d. Editing data or deleting matches when there is a date discrepancy between files (e.g., when the cancer diagnosis date is after the SRTR death date).

Other than the first item listed above, where cancer registries might inadvertently provide investigators with cancer records outside the calendar window of complete ascertainment, these steps together typically exclude far fewer than 1 percent of all records.

Some cancer registries that have conducted linkages for TCM have requested that we include only individuals in the SRTR who resided in their state, to simplify the linkage process. Other linkages, including the VPR linkages, have matched data in the SRTR for the entire U.S. transplant population with each cancer registry. We do not have complete information on individuals’ changes of address over time. Therefore, to keep analyses consistent, we consider individuals in the SRTR to reside for their entire period of cancer risk in the state/region where they lived when they were first reported to the SRTR. For instance, SOTRs who resided in Iowa at the time they entered on the transplant waitlist are considered to have lived in Iowa for their entire life both before and after transplantation. This assumption simplifies calculation of follow-up time at risk of cancer. As a result, we delete the subset of matches of Iowa SOTRs (in this example) to cancer registry records in other states. This approach also allows us to create a static dataset: we do not have to update the cancer data for SOTRs in Iowa every time the SRTR is matched to a different state cancer registry.

By ignoring the fact that some people move over time (i.e., “outmigration” if it occurs after registration in the SRTR) and deleting their matches to other cancer registries, we underestimate cancer incidence, but we have evidence that this deficit is small. In our initial article using TCM data,1 we estimated that outmigration was limited to 5.8 percent of SOTRs within 10 years of transplantation, based on an analysis of residence addresses for a limited sample. Also, we have analyzed data from 28 cancer registries that were linked to the entire SRTR through the VPR process. Of 43,715 total matched cancer cases that VPR cancer registries identified, only 1298 (3.0 percent) were in people who were not listed by the SRTR as residents of the respective cancer registry catchment area (e.g., an Idaho cancer case that matched to a person who was a New Mexico resident at the time of transplantation).

Before we incorporate data from a new cancer registry linkage into our study, we calculate standardized incidence ratios (SIRs) for each type of cancer in SOTRs using the new data (see SIR methods below). We then compare these new SIRs with the SIRs estimated by pooling all our other existing TCM registry data. We check that these SIRs are generally similar between the new and existing cancer registries across cancer sites, and, for overall cancer, that the 95 percent confidence interval for the SIR from the new data encompasses the overall SIR from all the other registries combined. This quality control step confirms the general validity of the new match under the assumption that the relative risk for cancer associated with transplantation does not vary substantially across cancer registry regions.

Transplant Cohort Definition

Most TCM Study analyses evaluate cancer risk among SOTRs using the linked cancer registry data. For these analyses, we restrict the transplant recipient cohort to individuals who resided in the catchment area of a participating cancer registry at the time of entry onto the wait list or (if that is missing) at transplantation.

Follow-up for cancer risk starts at the earliest of transplantation or start of cancer registry coverage. In some analyses, we include SOTRs who were transplanted before the start of cancer registry coverage; in those instances, such SOTRs begin their follow-up only at the start of cancer registry coverage (i.e., delayed entry after transplantation). In addition, for studies that include calculation of SIRs, we typically start follow-up no earlier than January 1, 1995, because we obtain general population cancer rates from SEER12 (which starts in 1995) to calculate expected counts.

Follow-up for cancer risk ends at the earliest of death, loss to follow-up by the SRTR, or end of cancer registry coverage. In many analyses, we additionally end follow-up at graft failure or re-transplantation. Kidney recipients who lose the function of their transplanted kidney can go back on dialysis, during which immunosuppression is much lower, so it can be important to exclude such person-time from some cancer risk estimates. If a person receives a subsequent transplant, that transplant is typically included again as a separate period of follow-up time.

Table 2 compares the characteristics of the U.S. SOTRs included in the TCM Study to those excluded. The TCM Study covers 459,263 SOTRs (69 percent of the U.S. total during 1995-2019). The included SOTRs resemble those who are excluded, except there are slight differences according to race/ethnicity (reflecting the geography of the participating cancer registries), and there are fewer included SOTRs in the most recent calendar period (largely due to the inclusion of data for 2018-2019 from only two cancer registries).

| Characteristic | Number of included transplants (% of total) | Number of excluded transplants (% of total) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 459,263 (100) | 205,972 (100) | |

| Sex |

Male | 284,053 (61.85) | 127,527 (61.91 |

|

Female | 175,210 (38.15) | 78,445 (38.09) | |

| Age at Transplant, years | 0-17 | 30,460 (6.63) | 11,580 (5.62) |

| 18-34 | 60,612 (13.20) | 24,690 (11.99) | |

| 35-49 | 125,387 (27.30) | 53,290 (25.87) | |

| 50-64 |

183,950 (40.05) | 84,304 (40.93) | |

| 65+ | 58,854 (12.81) | 32,108 (15.59) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | White, Non-Hispanic | 273,615 (59.58) | 134,219 (65.16) |

| Black, Non-Hispanic | 89,865 (19.57) | 40,160 (19.50) | |

| Hispanic | 67,579 (14.71) | 19,975 (9.70) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 23,795 (5.18) | 8,107 (3.94) | |

| Other, Unknown, Missing | 4,409 (0.96) | 3,511 (1.70) | |

| Transplanted Organ | Kidney |

268,121 (58.38) | 119,178 (57.86) |

| Kidney/Pancreas or Pancreas | 19,010 (4.14) | 8,714 (4.23) | |

| Liver | 96,577 (21.03) | 42,484 (20.63) | |

| Heart and/or Lung | 66,154 (14.40) | 30,743 (14.93) | |

| Other or Multiple | 9,401 (2.05) | 4,853 (2.36) | |

| Calendar Year of Transplant | 1995-1999 | 77,550 (16.89) | 21,612 (10.49) |

| 2000-2004 | 95,344 (20.76) | 26,007 (12.63) | |

| 2005-2009 | 107,205 (23.34) | 29,835 (14.48) | |

| 2010-2014 | 108,864 (23.70) | 29,988 (14.56) | |

| 2015-2019 | 70,300 (15.31) | 98,530 (47.84) | |

Standardized Incidence Ratios

To measure cancer risk in SOTRs relative to the general population, we calculate SIRs for cancer using incidence rates obtained from cancer registries. These expected rates are stratified by sex, age (5-year intervals), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander), and individual calendar year.

In our initial registry linkages, cancer registries provided a file of cancer cases for the entire population, not only those that matched to the SRTR. These files allowed us to calculate general population rates specific to each cancer registry region. However, cancer registries participating in the VPR linkages provide only the matched cases, so we are unable to use that approach. Instead, we now use SEER12 for cancer rates for all regions, and we have shown that these SIRs are generally similar to those calculated using registry-specific rates (see Table 3 below). For Kaposi sarcoma, we use SEER9 rates from 1973-1979 to avoid contamination of general population rates with cases from people with AIDS.2

| Cancer site | SIR (95% CI) using TCM cancer registry expected rates | SIR (95% CI) using SEER12 expected rates |

|---|---|---|

| Overall | 1.89 (1.87-1.92) | 1.81 (1.79-1.83) |

| Common cancers | ||

| Colorectum | 1.04 (0.98-1.11) | 1.03 (0.97-1.10) |

| Lung | 1.97 (1.90-2.04) | 2.08 (2.01-2.16) |

| Prostate | 0.88 (0.84-0.91) | 0.77 (0.74-0.81) |

| Kidney | 4.41 (4.20-4.61) | 4.42 (4.22-4.63) |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 4.68 (4.50-4.87) | 4.19 (4.03-4.35) |

Transplant Registry Variables

We use data provided by transplant centers in the SRTR to ascertain characteristics of SOTRs relevant for cancer incidence analyses, including basic demographic characteristics, details of the transplanted organ (e.g., the type of organ, sequence number), reason for transplantation, and the presence of certain viral infections (e.g., HIV, hepatitis B and C viruses, Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus). The SRTR also captures the HLA alleles of SOTRs and their donors at the A, B, and DR loci as well as the calculated mismatch score. The zip code of residence at the time of waitlisting or transplantation is available, and we have used this information to link to geographic measures of ultraviolet radiation exposure and socioeconomic status.3-6

The SRTR contains information on immunosuppressant medications prescribed at the time of initial hospital discharge, which we have used to assess associations with cancer incidence. These data include the specific medications used for induction and maintenance immunosuppression but not their doses. There are similar data available at follow-up intervals, but they are not considered to be complete or reliable, so we have focused on only the baseline regimen.

Reliance on SRTR data on baseline immunosuppressive medications is a limitation because we cannot assess dose or duration of these medications. People change medications over a period of several years, which leads to exposure misclassification. The SRTR has been linked to medication prescription claims databases, and we have collaborated with SRTR staff on specific projects to analyze those data,7, 8 which has allowed us to assess dose and duration of some medications. However, these prescription data are not routinely available for TCM studies.

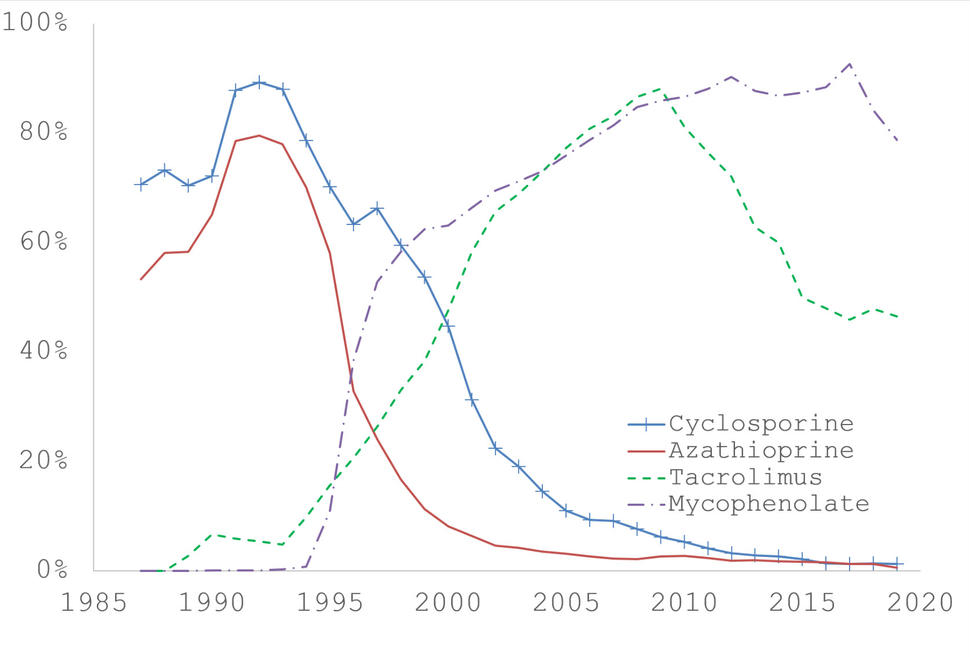

Among commonly used maintenance immunosuppression medications, cyclosporine and azathioprine were introduced in the earliest years and were commonly used together until the early 1990s, when their use declined. Starting in the mid-1990s, these two medications were gradually replaced by tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil, which are now commonly used together (see Figure 1 below, or download and read the underlying data from Figure 1). This pattern makes it difficult to assess cancer risk in relation to these medications individually. Instead, we have often used a combination medication variable that indicates whether an SOTR was receiving cyclosporine and/or azathioprine (but not tacrolimus or mycophenolate mofetil), tacrolimus and/or mycophenolate mofetil (but not cyclosporine or azathioprine), or another regimen not in one of these categories. Analyses using this approach and as well as for individual medications have identified some adverse cancer associations with the older medications, especially for cutaneous cancers.3, 9, 10

The SRTR collects information from transplant providers on malignancies that were diagnosed prior to transplantation (prevalent) or during follow-up after transplantation (incident). However, we showed in a comparison of the SRTR data with cancer registry diagnoses that agreement was poor and that the SRTR missed a large fraction of cancer cases (sensitivity 52.5%).11 We therefore do not use the SRTR cancer diagnoses in most analyses.

An exception is when the SRTR records a diagnosis of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) or basal cell carcinoma (BCC) after transplantation. Cutaneous SCC incidence is greatly elevated in SOTRs, and these cancers can be highly aggressive. Cancer registries do not record diagnoses of cutaneous SCC or BCC. We and others have shown that the SRTR misses a large fraction of SCC and BCC diagnoses (sensitivity 14-41%) but that the positive predictive value of SRTR diagnoses of these cancers is relatively high (71-88%).12,13 We have therefore used SRTR diagnoses of cutaneous SCC in some studies, both as an indicator of sensitivity to ultraviolet radiation and increased susceptibility to skin cancer5,10,12 and as a cancer outcome.8

Additional TCM Data Resources

For selected projects, we have worked with registry collaborators to obtain additional data. As mentioned above, we have worked with SRTR staff to analyze linked medication prescription claims.7, 8 In addition, we have obtained deidentified pathology reports from cancer registries to extract detailed information (e.g., tumor biomarkers) on cancer cases of interest.14

We have also worked with cancer registry collaborators to obtain formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tumor tissues for cancers arising in SOTRs. Two participating TCM cancer registries (Hawaii and Iowa) maintain repositories of tumor tissues discarded by hospitals in their catchment areas. These registries and a few other TCM cancer registries will also endeavor retrieve specified tumor blocks retained in hospital pathology departments. The process for obtaining such tumor samples is complex and involves extended collaborative effort over a period of several years. We used this approach to assemble the largest collection of bladder cancer specimens from SOTRs (N=44 cases). This collection of tumors allowed us to evaluate bladder cancers in SOTRs for the presence of carcinogenic viruses and characterize other tumor genomic features (Starrett et al., submitted).

Transplant centers provide information on causes of death in SOTRs and waitlist candidates, which is obtained through medical records. However, information may be incomplete or unreliable if the death occurs at an outside hospital, and the SRTR uses a nonstandard coding system to classify causes of death. We have therefore linked the SRTR to the National Death Index to obtain information from death certificates on causes of death. These data allow evaluation of mortality due to cancer, COVID-19, and other serious medical conditions associated with end-stage organ disease and transplantation (Wang et al., and Volesky et al., submitted).

Human Subjects and Data Security Considerations

HRSA and its contractor manage the SRTR data as part of their federally mandated role overseeing the US solid organ transplant network. These data are used by HRSA and the transplant community to study transplant outcomes and generate reports that guide transplant practice and improve patient safety. Because HRSA’s role in the study falls under its administrative oversight duties, its activities under the TCM Study are IRB exempt.

NCI investigators receive only deidentified data from HRSA, its contractor, and cancer registries. NCI initially obtained IRB approval for its participation in this study, and a waiver of informed consent was granted by the NCI IRB. However, in April 2020 the NIH IRB determined that the TCM Study is not human subjects research, so NIH IRB review was terminated. Data use agreements between NCI, HRSA, and cancer registries preclude release of TCM Study data to outside researchers.

NCI researchers analyze TCM data only on password-protected network servers. Researchers sign a confidentiality agreement indicating that they will keep the data secure, will not try to identify patients, and will not publish results that could be used by others to identify patients. Manuscripts are circulated to registry collaborators prior to submission for routine review to further ensure that publication will not lead to inadvertent identification of patients.

Bibliography

- Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, Fraumeni JF, Jr., Kasiske BL, Israni AK, Snyder JJ, et al. Spectrum of cancer risk among US solid organ transplant recipients. JAMA. 2011;306(17):1891-901.

- Chaturvedi AK, Mbulaiteye SM, Engels EA. Underestimation of relative risks by standardized incidence ratios for AIDS-related cancers. Ann Epidemiol. 2008 Mar.

- Clarke CA, Robbins HA, Tatalovich Z, Lynch CF, Pawlish KS, Finch JL, et al. Risk of merkel cell carcinoma after solid organ transplantation. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(2).

- Cahoon EK, Linet MS, Clarke CA, Pawlish KS, Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM. Risk of Kaposi sarcoma after solid organ transplantation in the United States. Int J Cancer. 2018;143(11):2741-8.

- Sargen MR, Cahoon EK, Yu KJ, Madeleine MM, Zeng Y, Rees JR, et al. Spectrum of Nonkeratinocyte Skin Cancer Risk Among Solid Organ Transplant Recipients in the US. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158(4):414-25.

- Geris JM, Spector LG, Pfeiffer RM, Limaye AP, Yu KJ, Engels EA. Cancer risk associated with cytomegalovirus infection among solid organ transplant recipients in the United States. Cancer. 2022;128(22):3985-94.

- Yanik EL, Gustafson SK, Kasiske BL, Israni AK, Snyder JJ, Hess GP, et al. Sirolimus use and cancer incidence among US kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2015;15(1):129-36.

- D'Arcy ME, Pfeiffer RM, Rivera DR, Hess GP, Cahoon EK, Arron ST, et al. Voriconazole and the Risk of Keratinocyte Carcinomas Among Lung Transplant Recipients in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(7):772-9.

- Robbins HA, Clarke CA, Arron ST, Tatalovich Z, Kahn AR, Hernandez BY, et al. Melanoma Risk and Survival among Organ Transplant Recipients. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135(11):2657-65.

- Laprise C, Cahoon EK, Lynch CF, Kahn AR, Copeland G, Gonsalves L, et al. Risk of lip cancer after solid organ transplantation in the United States. Am J Transplant. 2019;19(1):227-37.

- Yanik EL, Nogueira LM, Koch L, Copeland G, Lynch CF, Pawlish KS, et al. Comparison of Cancer Diagnoses Between the US Solid Organ Transplant Registry and Linked Central Cancer Registries. Am J Transplant. 2016;16(10):2986-93.

- Zamoiski RD, Yanik E, Gibson TM, Cahoon EK, Madeleine MM, Lynch CF, et al. Risk of Second Malignancies in Solid Organ Transplant Recipients Who Develop Keratinocyte Cancers. Cancer Res. 2017;77(15):4196-203.

- Garrett GL, Yuan JT, Shin TM, Arron ST. Validity of skin cancer malignancy reporting to the Organ Procurement Transplant Network: A cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017.

- Mahale P, Weisenburger DD, Kahn AR, Gonsalves L, Pawlish K, Koch L, et al. Anaplastic large cell lymphoma in human immunodeficiency virus-infected people and solid organ transplant recipients. Br J Haematol. 2021;192(3):514-21.