Bringing the Pieces Together: CCR-DCEG FLEX Awards

, by Elise Tookmanian, Ph.D.

To capitalize on the complementary research approaches of the Center for Cancer Research (CCR) and DCEG, the CCR-DCEG FLEX award was established in 2015 to fund collaborative projects. Seven years later, Drs. Constanza Camargo, Charles Rabkin, Eric Engels, Neelam Giri, and Laufey Amundadottir, discuss how their projects came about and their progress toward understanding the causes of cancer and the means of prevention.

2015: Establishing a Collaborative Intramural Award

Conducting research that spans scientific disciplines is central to the mission of DCEG. This commitment to collaboration led to the establishment of the Trans-Divisional Research Program with the express purpose of facilitating research across the different branches within DCEG. Beyond the division, DCEG researchers also collaborate with other researchers across the National Cancer Institute (NCI), National Institutes of Health, other federal agencies, the U.S., and the world.

Within the NCI, the DCEG collaborations with CCR have been especially fruitful due to their complementary research approaches. While DCEG tends to approach research questions using population-based epidemiological studies, CCR uses basic biological and clinical approaches. When these approaches are used together strategically toward a common research goal, ground-breaking discoveries are possible.

The CCR-DCEG FLEX award was established in 2015 to fund these important collaborative projects between DCEG and CCR researchers. Seven teams have received funding for their research on cancer mechanism, diagnosis, prognosis, susceptibility, predisposition, or prevention. In 2022, the award expanded to fund health disparities research with separate collaborative Health Disparities Awards.

Almost seven years later, we take a look at some of the CCR-DCEG FLEX award projects and their progress toward understanding the causes of cancer and the means of prevention. Research does not often take a straightforward path, and these projects are no exception. However, as we’ll see, it is often the surprises and even setbacks, that lead to creative solutions and progress.

2016: It Takes a Village - Creating a Helicobacter pylori Research Resource

For most of their careers, Charles Rabkin, M.D., senior investigator in the Infections and Immunoepidemiology Branch (IIB), and Maria Constanza Camargo, Ph.D., Earl Stadtman investigator in the Metabolic Epidemiology Branch (MEB), have been studying the molecular epidemiology of gastric cancer. Chronic infection by the bacterium Helicobacter pylori causes the most common type of gastric cancer. However, only a small percentage of H. pylori infections will lead to cancer because not all strains of H. pylori are the same. There is incredible genomic variability between strains, and sequence differences in a few genes have been linked to carcinogenicity.

Based on these known observations, Drs. Rabkin and Camargo envisioned a broader initiative to understand how differences between strains affect carcinogenicity. In 2016, they received the inaugural DCEG-CCR FLEX Award, which funded the creation of the H. pylori Genome Project (HpGP), in collaboration with CCR investigator Ding J. Jin, Ph.D., in the Gene Regulation and Chromosome Biology Laboratory. In this project, H. pylori specimens from about 50 countries were collected from patients with various gastric conditions. Study samples represent low and high gastric cancer risk populations. “It took years to collect and process the specimens from the approximately 70 collaborating centers. The HpGP is based on viable single colonies of H. pylori, which take time, effort and expertise to isolate,” said Dr. Camargo.

The DCEG Cancer Genomics Research Laboratory (CGR) carries out the molecular characterization of the strains using SMRT/PacBio technology. While genomic sequencing of these strains is a standard procedure, Dr. Rabkin was excited to add epigenomic characterization which, “capitalized on newly available technology for determining DNA base modifications.” To acquire these strains and analyze the wealth of data, an international HpGP network was formed, involving investigators from Asia, Europe, and the Americas.

The award proposal included plans for Dr. Jin to carry out mechanistic studies. However, when he moved on from the NCI within the first year, Drs. Rabkin and Camargo continued to pursue the basic science side of this project with the help of outside collaborators from multiple disciplines. Together with the Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, they built a biobank of over one thousand strains as a resource for the scientific community. “There are draft manuscripts in the works on key features of the H. pylori genome that may contribute to understanding gastric cancer etiology, including its prophages, plasmids, and restriction-modification systems,” said Dr. Rabkin. As this resource grows and analysis is completed, Drs. Rabkin and Camargo hope to be closer to understanding the molecular determinants of H. pylori carcinogenicity.

2018: Matching Expertise – The Transplant Cancer Match Study and Virology

Eric A. Engels, M.D., M.P.H., senior investigator and chief of IIB, has a longstanding interest in understanding cancers in immunosuppressed populations, such as solid organ transplant recipients. He leads the Transplant Cancer Match (TCM) Study, which links national registries of cancer and transplant patients.

From the TCM Study, Dr. Engels observed an elevated risk of bladder cancer in kidney transplant recipients who had evidence of kidney damage from BK polyomavirus. It seemed possible that in some solid organ transplant recipients, their immunosuppressed state allowed the BK polyomavirus to be reactivated and potentially cause bladder cancer. A few studies seemed to support this hypothesis, describing detection of these viruses in bladder cancers from solid organ transplant recipients.

“I discussed our preliminary finding with two researchers in CCR, and together we decided to obtain and test our own series of tumors,” said Dr. Engels. These CCR researchers were two virologists, Christopher B. Buck, Ph.D., and Gabriel Starrett, Ph.D., in the Laboratory of Cellular Oncology. In 2018, this interdisciplinary team received the DCEG-CCR FLEX Award.

This award along with the expertise of the group and collaborators in the TCM Study, helped this team to carry out the largest study of this kind to date. More than 30 tumors from solid organ transplant recipients were sequenced. “The TCM Study was uniquely valuable for this, because the national linkage with cancer registries allowed us to identify and retrieve a large number of tumors that had previously arisen in transplant recipients,” noted Dr. Engels.

They found evidence of BK polyomavirus in about 25 percent of cases and characterized features of the tumors with BK polyomaviruses present, including DNA mutations and gene expression. “Drs. Buck and Starrett’s knowledge and experience were invaluable in analyzing and interpreting the genomic data we obtained from these tumors,” said Dr. Engels. A manuscript describing these results is currently under review.

2020: Thinking Bigger – Expanding Fanconi Anemia Research

Patients with Fanconi anemia (FA), a rare inherited genetic disorder that affects the body’s ability to repair damaged DNA, have dramatically higher risk for certain types of cancer. Studies conducted by Blanche Alter, M.D., M.P.H, retired senior investigator and current special volunteer and Neelam Giri, M.D., M.B.B.S., staff clinician in the Clinical Genetics Branch (CGB) showed that head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) is the most frequent and deadly cancer type in these patients, occurring at much younger ages (median 26 years of age) and higher frequencies than in the general population. Meanwhile, other researchers have been testing whether the diabetes drug, metformin, can stop the progression of oral precancerous lesions to cancer in non-FA models, with promising results from the lab, animal studies, and some preliminary results in patients. Metformin inhibits a pathway (mTOR signaling) that is highly active in HNSCC.

Based on these results, Drs. Giri and Alter wanted to test whether metformin could stop cancer progression in patients with FA. “In DCEG we do epidemiological studies, not treatment trials,” said Dr. Giri. “In partnership with CCR, we were planning to explore a potential chemoprevention treatment trial for these high-risk patients.” CCR senior investigator, Rosandra N. Kaplan, M.D., of the Pediatric Oncology Branch and J. Silvio Gutkind, Ph.D., of Moores Cancer Center at the University of California, San Diego, were the first investigators to join the team. In 2019, the group’s Bench to Bedside proposal was funded to begin metformin studies in a mouse model of FA, and in 2020, they received the DCEG-CCR FLEX award to support future metformin trials in patients with FA.

Unfortunately, before they could begin in earnest, the COVID-19 pandemic halted the clinical research component. Despite this setback, over the next two years, the scope of the study changed from a small cohort of patients with FA with oral lesions to a comprehensive study of adolescents and adults with FA at risk of HNSCC with a goal of enrolling around 150 participants for prospective longitudinal cancer screening, oral brush biopsies, and biomarker studies. This expansion was made possible by a partnership with the Fanconi Anemia Research Fund, which made a million-dollar investment in the study.

As part of the longitudinal cancer screening, participants will undergo biannual HNSCC screening. Biospecimens from the oral brush biopsies will undergo extensive genomic, epigenetic, transcriptomic, biomarker, and microbiome analysis. The team has also expanded to include collaborators with expertise in these areas, such as microbiome research (Emily Vogtmann, Ph.D., M.P.H, Earl Stadtman investigator in MEB) and DNA cytometry (British Columbia Oral Cancer Prevention program). If the results of the metformin studies in the FA mouse model indicate tumor suppression, a metformin prevention/early intervention trial may be developed for patients with FA to test whether it can reduce the progression to HNSCC in this very high-risk population.

“If the COVID-19 pandemic hadn't happened, the study would be much smaller, and less comprehensive. We are optimistic that the updated study design will yield important insights into HNSCC etiology and, hopefully, future cancer prevention studies in FA,” said Dr. Giri. The team hopes to begin recruitment in October of 2022.

2021: Divide and Conquer - Understanding Pancreatic Cancer by Cell Type

Laufey Amundadottir, Ph.D., senior investigator in the Laboratory of Translational Genomics is interested in the genetic factors that underly the risk of pancreatic cancer. She co-leads the Pancreatic Cancer Cohort Consortium (PanScan), an international genome-wide association study for pancreatic cancer. While PanScan has identified a number of novel genetic variations associated with the often fatal malignancy, Dr. Amundadottir has been interested in the underlying mechanisms: how do these changes influence risk? Genetic regulation is one possible mechanism, especially since many of the genetic variants occur in non-coding regions of the genome.

While Dr. Amundadottir has studied the genetics of gene regulation in bulk tissues, she knew this approach was limiting her ability to explore fully the many different pancreatic cell types: acinar cells and duct cells of the exocrine pancreas and the alpha, beta, and delta cells of the endocrine pancreas. Looking at a mix of these cells at the same time could obscure a change in genetic regulation happening in only one cell type.

During the fifth NCI Pancreatic Cancer Conference in 2018, CCR Stadtman investigator, H. Efsun Arda, Ph.D., in the Laboratory of Receptor Biology and Gene Expression, presented on a technique she developed to separate the pancreas cells by type using antibodies to cell surface antigens and cell sorting and described her interest in the gene regulatory networks of pancreatic cells. Just over an hour later, Dr. Amundadottir gave her talk on common inherited factors associated with pancreatic cancer risk. “I listened to her, she listened to me, and we realized, this is a match made in heaven,” said Dr. Amundadottir.

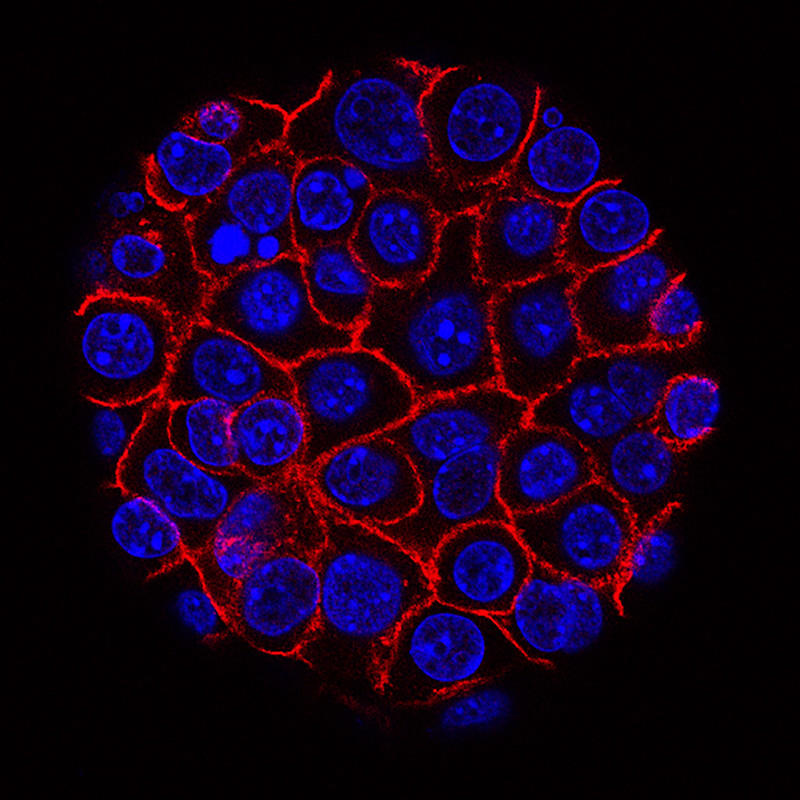

“Our research interests really align, so we started talking about opportunities to work together and applied for the CCR-DCEG Award,” she continued. Together, they devised a project where Dr. Arda’s lab would process pancreas tissue samples by cell type followed by digestion to release the DNA and RNA in order to profile the transcriptome, genome, epigenome, and open chromatin. With this wealth of data, including information about the donor, they hope to uncover how genetic variation affects gene regulation, and potentially their relation to pancreatic carcinogenesis. In 2021, their project was funded.

One year later, their research is well underway. They have processed and begun analyzing tissue samples from about 50 donors, half of the number they plan to collect. “Joining forces helps us do more than we could alone,” said Dr. Amundadottir. “We have joint lab meetings which have been really helpful to the postdocs in both our groups.”

Beyond their scientific progress, the collaboration also led to an unexpected mentoring relationship. “When we met, I had been tenured for a few years, but [Dr. Arda] was brand new. She has mentioned to me that it’s very helpful to have someone who’s been here for a little while, who can direct her to resources and be a mentor to her,” said Dr. Amundadottir. She was reminded of one of her early mentors, Patricia Hartge, Sc.D., M.A., Scientist Emerita, who began the PanScan consortium. “I learned a lot from her,” Dr. Amundadottir said. “Now I’m giving back something that's been given to me in the past.”